What is Carrier Screening?

Carrier testingCarrier testing can determine if a person carries one of the altered genes that cause a recessive disease. DNA carrier testing establishes the presences or absences of particular mutation(s). Enzymatic testing evaluates the level of activity of an enzyme, which when absent causes disease. In some diseases the enzyme test is not sensitive enough to determine carrier status. More is a type of genetic testing done to find out if you carry a change in a geneOften referred to as the "unit of heredity." A gene is composed of a sequence of DNA required to produce a functional protein. More that can cause a specific genetic disease. Most often, being a carrier for one of these changes does not mean that you have the genetic disease yourself, but that you may have a chance to pass it on to a child.

Depending on the type of carrier screening, the test could use a sample of blood, saliva, or tissue from inside the cheek.

For Tay-Sachs carrier screening specifically, current data supports the use of a test called gene sequencing to identify whether an individual is a carrier. To learn more about this data and other kinds of screening tests, check out NTSAD’s 2019 position statement here.

Why is Carrier Screening Important?

It’s possible to carry a change in a gene for a genetic disease without any signs or symptoms.

When carrier screening is done before pregnancy, it helps you determine the chances of having a child with a rare genetic disease.

Anybody Can Be a Carrier

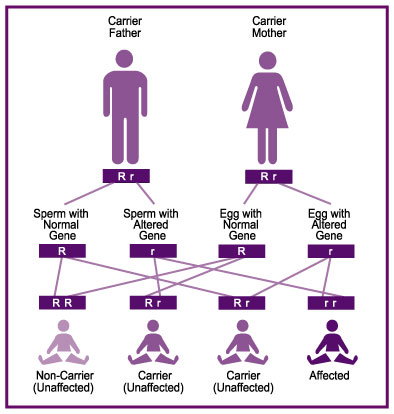

Every person carries two copies of each gene in their body, one inherited from each parent. Tay-Sachs, Canavan, GM1, and Sandhoff diseases are autosomal recessiveDescribes a trait or disorder requiring the presence of two copies of a gene mutation at a particular locus in order to express observable phenotype; specifically refers to genes on one of the 22 pairs of autosomes (non-sex chromosomes). More diseases. This means that a person must inherit two changes in the gene that causes the disease, one in each of their gene copies. Therefore, both parents must carry a change in the same gene to have a chance of both passing on those changes to an affected child.

If you and your partner are carriers for the same recessive disease, there’s a 25% chance that your child will be affected with the disease—even if you already have a child who is unaffected. If one or both parents are a carrier of a recessive disease, there is a 50% chance that your child will also be a carrier.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the carrier rates among the general United States population are:

- Tay-Sachs: 1 in 250 people

- Canavan: 1 in 300 people

- GM1: 1 in 250 people

- Sandhoff: 1 in 600 people

Prevalence of Tay-Sachs Disease

While anybody could be a carrier of Tay-Sachs, there is a higher prevalence of the disease among some populations.

About 1 in 27 people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent is a carrier of Tay-Sachs disease. If you have Ashkenazi heritage, it’s a good idea to be screened, even if your partner is not Jewish.

People of Irish, Cajun, French Canadian, and Pennsylvania Dutch heritage also experience higher levels of Tay-Sachs disease in their populations.

Family Connection

If someone in your family or your partner’s family has Tay-Sachs, Canavan, GM1, or Sandhoff disease, you may consider undergoing carrier screening.

There are several different types of carrier tests that are available.

If you have a specific family history of a genetic disease, you may be offered a targeted test to determine whether you are a carrier for that disease.

Expanded carrier screening is another kind of carrier test. It tests whether you are a carrier for many different genetic diseases, especially diseases where it is more common in the general population to be a carrier.

You may also hear about whole exome sequencing. This is a test that looks at all the genes in your body to see whether you carry any changes.

By the same token, if carrier screening shows that you or your partner are carriers of a rare disease, it is recommended to share this information with blood relatives, so they can decide if they wish to be tested.

Your genetic counselor or clinician can help to provide you with resources for sharing this information about your test results with blood relatives.

How to Start the Carrier Screening Process

If you’re interested in genetic carrier screening, you can mention it during an appointment with your healthcare provider or OB-GYN. Be sure to discuss your family history, any genetic disease in your family, and your ancestry. Your clinician or OB-GYN will be able to order carrier screening tests for you and your partner.

You can also ask them about a referral for an appointment with a genetic counselor or locate a genetic counselor directly (see below), who will collect your family history information and help order carrier screening.

Contact your health insurance company to ask:

- If it covers carrier screening

- If you need a clinician referral for a genetic counselor

How to Find a Genetic Counselor

A genetic counselor may collect your medical and family history, discuss your personal risks for genetic disease, and provide you with more information about carrier screening or other kinds of genetic tests. They will guide you through deciding about testing, help you understand the results, explain the options and resources available to you, and support you as you decide what to do next.

Depending on your health insurance, you may need a referral for a genetic counselor or you may be able to contact a genetic counselor directly.

Some genetic counselors support clients in person and others can provide their services virtually.

You can use the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) directory to find a genetic counselor in the United States.

Frequently Asked Questions

You are encouraged to talk to your healthcare provider or OB-GYN about carrier screening if you’re thinking about starting a family or if someone in your family has Tay-Sachs, Canavan, GM1, or Sandhoff disease.

For more information, please see our FAQ below or email Becky Benson (becky@ntsad.org), Family Services Manager or Diana Jussila (diana@ntsad.org), Director of Family Services.

General Topics

Yes. Anybody could be a carrier. Even if your partner is not Jewish it is still possible that you are both carriers for the same recessive condition. Discuss screening options with your healthcare provider or genetics professional (geneticist or genetic counselor) to determine the best screening method for you and your partner.

It’s important for you to speak with a genetics professional prior to having carrier screening. Through some programs, a saliva sample can be collected at home and sent to a laboratory for analysis. Saliva testing does not include Tay-Sachs enzymeAccording to Genome.gov, an enzyme is a biological catalyst and is almost always a protein. It speeds up the rate of a specific chemical reaction in the cell. The enzyme is not destroyed during the reaction and is used over and over. More analysis, but may provide sequencing of multiple genes.

Yes. If you and your partner are carriers for the same recessive disease, there is a 25% chance with each pregnancy that your child will be affected with the disease as well as a 75% chance of having an unaffected child. Two carrier parents could have several healthy children before having an affected child.

It is best to talk with your healthcare provider or make an appointment with your genetics professional to discuss your interest in carrier screening. Each of these medical professionals can explain the screening, submit an order, and interpret the results for you.

Natural history studies document the progression of the disease. The more data there is about the progression of the disease from medical data and patient experience, the clearer the endpoints are to determine whether a therapy is working or not. The PIN is a format to help families contribute this information. Therefore, participating in the PIN and natural history studies is important and critical.

Join the GM2 Tay-Sachs & Sandhoff PIN here or the GM1 PIN here as soon as you can!

Inclusion criteria are necessary for a successful clinical trial. Inclusion criteria also help minimize risk in a clinical trial and ensure the proposed therapy is safe and effective. Having a successful trial in which risks are minimized and success of the therapy can be shown is important to allow therapies to continue in future trials and to lead to eventual approval.

Tay-Sachs Disease

Current data supports the use of gene sequencing for Tay-Sachs carrier screening in individuals of all ethnic backgrounds. Enzyme testing is also considered to be another reliable method of carrier screening for Tay-Sachs.

To learn more about these recommendations, please reference the NTSAD 2019 position statement on Standards for Tay-Sachs Carrier Screening, found here.

Some labs also offer expanded carrier screening panels with many conditions. Discuss your interest in carrier screening with your genetics professional to determine which testing is best suited for you.

Yes. It’s important to remember that anyone could be a carrier for Tay-Sachs disease. You are at risk of being a carrier of a Jewish mutationA change in the sequence of DNA. Many mutations are "silent" and do not cause disease. When mutations occur in genes and disrupt the production of a functional protein, they may lead to genetic disease. More based on your Jewish ancestry. Individuals of Irish, Cajun, French Canadian, and Pennsylvania Dutch descent are also at increased risk of having a Tay-Sachs disease mutation. It may be a good idea for you to have an expanded panel that includes screening for other recessive conditions. Discuss your options with your genetics professional prior to testing.

Yes, you can get carrier screening for Tay-Sachs disease while pregnant. When women are pregnant or taking birth control pills, detection is best using leukocytes. Make sure that the genetics professional ordering your carrier screening knows that you are pregnant so that the correct testing is ordered. The father of the pregnancy can also pursue carrier screening to determine if he is a carrier. If the father is not found to be a carrier, your baby is at very low risk for Tay-Sachs disease. If he is carrier, you can consider doing an

amniocentesisA procedure used for prenatal diagnosis, which involves insertion of a needle through the abdomen into the amniotic fluid. This procedure is performed using ultrasound guidance, and allows the physician to obtain a small amount of amniotic fluid which can then be used for testing. Amniocentesis is usually performed between 16 and 18 weeks of pregnancy, but some centers offer "early amnio" at 14 weeks of pregnancy. More or

chorionic villus samplingA procedure used for prenatal diagnosis, which involves insertion of a needle through the abdomen into fingerlike projections of the placenta which are called chorionic villi. This procedure is also performed using ultrasound guidance, and testing can be performed with the tissue obtained. Depending upon the location of the placenta, the tissue may be obtained transvaginally rather than abdominally, by inserting a catheter through the cervix and into the uterus. CVS is usually performed at 10 to 12 weeks of pregnancy. More (CVS). These are diagnostic tests that will be able to tell you if your current pregnancy is affected with Tay-Sachs disease or is unaffected. Speak with your obstetrician or genetics professional about this testing.

For more information, visit Family Planning.

A “pseudodeficiency allele” reduces enzyme activity but does not cause a disease. A pseudodeficiency allele does not cause Tay-Sachs disease in a carrier or in the children who inherit the pseudodeficiency allele. Even if a person has one Tay-Sachs mutation and one pseudodeficiency allele, they will not develop Tay-Sachs disease. Approximately 30% of non-Ashkenazi Jewish and 3% of Ashkenazi Jewish individuals who are identified as carriers by enzyme analysis have a benign pseudodeficiency allele.

Yes. Tay-Sachs disease enzyme analysis is very sensitive but can be affected by pregnancy status, medications, and transport temperature.

DNAThe chemical sequence found in genes, and which allows for the transmission of inherited information from generation to generation. More mutation analysis may help clarify whether an individual is truly a carrier for Tay-Sachs disease. Typically DNA and enzyme testing are performed at the same time to allow for optimal interpretation of results.

A genetics professional can help you to understand what this result means for you and your family. You can use the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) directory to find a genetic counselor in the United States.

A combination of DNA and enzyme testing is strongly recommended for Tay-Sachs screening for the highest level of detection. Most labs only offer DNA testing for Tay-Sachs. Be sure to request a laboratory that performs both DNA and enzyme testing.

It is also important that your genetic screening is tailored to you and your family history. For example, individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry are known to have different mutations than individuals from the French Canadian population. It’s important to make sure that you do carrier screening specific to your ancestry.

Some labs offer expanded panels with many conditions aimed at couples with mixed or unknown ancestry. Discuss your interest in carrier screening with your genetics professional and determine which testing is best suited for you.

Yes. It’s important to remember that anyone could be a carrier for Tay-Sachs disease. You are at risk of being a carrier of a Jewish mutation based on your Jewish ancestry. Individuals of Irish, Cajun, French Canadian, and Pennsylvania Dutch descent are also at increased risk of having a Tay-Sachs disease mutation. It may be a good idea for you to have an expanded panel that includes screening for other recessive conditions. Discuss your options with your genetics professional prior to testing.

Yes, you can get carrier screening for Tay-Sachs disease while pregnant. When women are pregnant or taking birth control pills, detection is best using leukocytes. Make sure that the genetics professional ordering your carrier screening knows that you are pregnant so that the correct testing is ordered. The father of the pregnancy can also pursue carrier screening to determine if he is a carrier. If the father is not found to be a carrier, your baby is at very low risk for Tay-Sachs disease. If he is carrier, you can consider doing an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS). These are diagnostic tests that will be able to tell you if your current pregnancy is affected with Tay-Sachs disease or is unaffected. Speak with your obstetrician or genetics professional about this testing.

For more information, visit Family Planning.

A “pseudodeficiency allele” reduces enzyme activity but does not cause a disease. A pseudodeficiency allele does not cause Tay-Sachs disease in a carrier or in the children who inherit the pseudodeficiency allele. Even if a person has one Tay-Sachs mutation and one pseudodeficiency allele, they will not develop Tay-Sachs disease. Approximately 30% of non-Ashkenazi Jewish and 3% of Ashkenazi Jewish individuals who are identified as carriers by enzyme analysis have a benign pseudodeficiency allele.

Yes. Tay-Sachs disease enzyme analysis is very sensitive but can be affected by pregnancy status, medications, and transport temperature. DNA mutation analysis may help clarify whether an individual is truly a carrier for Tay-Sachs disease. Typically DNA and enzyme testing are performed at the same time to allow for optimal interpretation of results.

A genetics professional can help you to understand what this result means for you and your family. You can use the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) directory to find a genetic counselor in the United States.

Genetic Testing Terminology

If you think of a gene as a page in a book, “gene sequencing” refers to reading across each letter of that page to see if there are any “spelling mistakes” in the genetic code. Gene sequencing would detect if “cat” in the book is misspelled as “ctt”. Some coding changes are normal and make us unique individuals. Other coding differences can result in disease.

A “variant of uncertain significance” or VUS is a coding change in your genes that has not been seen in enough people to thoroughly understand. We all have genetic variants that make us unique individuals. Some variants in your genes are normal and do not affect your health. It is also possible that a variant will eventually explain a disease in your family or increase your chance of having a child with a genetic disease.

Researchers are working to classify these variants and clarify what they mean for your family’s health. Most often a variant of uncertain significance is eventually determined to be “benign” or normal. It is a good idea to check in with your genetics professional every few years to see if there are updates on your specific variant.

Known Carrier of Tay-Sachs Disease

No. Carriers do not express the symptoms of the disease. You need two mutated copies of a particular gene, one inherited from each parent, to develop an autosomalRefers to genes that are not found on the sex chromosomes. Those chromosomes that are not XX and XY, i.e. sex-linked. More recessive disease like Tay-Sachs or an allied disease.

Carrier screening is not recommended for children under the age of 18, as it is not helpful in the medical care of healthy children. Once your children are 18 or older they can decide if they would like to pursue carrier screening, prior to considering reproductive options.

There are many reproductive options available to increase your chance of a having a healthy baby, specifically a baby that does not have Tay-Sachs disease. Some people choose adoption, others use sperm, egg, or embryo donation from non-carriers. Some pursue a natural pregnancy with prenatal testing by amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS). Some consider in vitro fertilization with

pre-implantation genetic diagnosisTests early-stage embryos produced through in vitro fertilization (IVF) for the presence of a variety of genetic conditions. One cell is extracted from the embryo in its eight-cell stage and analyzed. Embryos free of conditions that would cause serious disease can be implanted in a woman's uterus with the hopes of resulting in a healthy pregnancy. More (PGD).

For more information, visit the Family Planning page.

Both parents need to be carriers for a child to be affected with an autosomal recessive disease like Tay-Sachs. However, there is a 50% chance with each pregnancy that your child will be a carrier (like you) and a 50% chance that your child will inherit two normal copies of the Tay-Sachs gene.

Finding out that you are a carrier while pregnant can be anxiety provoking. Fortunately, you have several options that will help you better understand the risk to your baby.

The father of the pregnancy can pursue carrier screening to determine if he is also a carrier. If the father is not found to be a carrier, your baby is at very low risk for Tay-Sachs disease. If he is carrier, you can consider doing an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS). These are diagnostic tests that will be able to tell you if your current pregnancy is affected with Tay-Sachs disease or is unaffected. Speak with your obstetrician or genetics professional about this testing.

Other Issues of Concern

If your relative had a baby with Tay-Sachs disease, he or she is a carrier. If this is a blood relative, you may be at increased risk of being a carrier. It’s a good idea to discuss this family history information with your doctor or genetics professional. Remember, you are only at risk of having a child with Tay-Sachs disease if both you and your partner are carriers.

Carriers of French Canadian descent are more likely to have a mutation called a deletion; this means that a region of the HEXA gene is missing. If you think of the HEXA gene as a page in a book, screening by sequencing is only looking for single letter typos, but can fail to detect missing paragraphs. If you are French Canadian, ask your doctor or genetics professional to order genetic testing that will be able to find a large deletion, if present.

All individuals with Tay-Sachs disease have a mutation in both copies of their HEXA genes. Some individuals with late onset Tay-Sachs disease have one late onset mutation and one infantile onset mutation. Others have two late onset mutations. If you have one infantile onset mutation and your partner does too, there is a 25% chance with each pregnancy that your child will have infantile or juvenile Tay-Sachs. If you have two late onset mutations and your partner is a carrier for late onset Tay-Sachs disease, your children are at risk for late onset Tay-Sachs, but not early onset disease.